Amazing Grace: Galatians 5: 1 – 12

This week I want to start the blog with a bit of a personal reflection. Yesterday was Ash Wednesday. Traditionally it is a day of fasting, confession and repentance.

I grew up in a Christian household. We did pancake Tuesday, and I will not be persuaded otherwise that my dad makes the best pancakes in the world. But it had no religious significance for us. I don’t think I was aware of Ash Wednesday until I went to university and had to question why I saw people walk around with black crosses on their foreheads. Growing up we were all about Easter, all about resurrection and victory.

Learning from others

As I’ve become older, and as I’ve met and become friends with Christians from different traditions, I’ve grown in my curiosity of, and appreciation for the festivals and rhythms of the ‘Christian Calendar’, especially the season of Lent (which starts with Ash Wednesday).

Don’t worry for the Chocolatiers

I suspect that for most people if they associate Lent with anything they associate it with giving up something. But worry not for the Chocolatiers whose sales take a hit as millions give up chocolate for 40 days; they have convinced even more people that the “proper” way to celebrate Easter is to overindulge in that from which you have just abstained, and so their profits grow as waistlines expand.

Taking up for Lent

Around 2010 I became aware of people suggesting that rather than give up something for Lent we should take on something. My ‘taking on” for Lent started in 2011 with Stephen Cherry’s book Barefoot Disciple. Each year the Archbishop of Canterbury commissions someone to write a book for Lent, and this was the book for 2011. If you’ve read Ruth Valerio’s Saying Yes to Life – and I know a number of you have – then you have read one of the Archbishop’s Lenten books.

Around 2010 I became aware of people suggesting that rather than give up something for Lent we should take on something. My ‘taking on” for Lent started in 2011 with Stephen Cherry’s book Barefoot Disciple. Each year the Archbishop of Canterbury commissions someone to write a book for Lent, and this was the book for 2011. If you’ve read Ruth Valerio’s Saying Yes to Life – and I know a number of you have – then you have read one of the Archbishop’s Lenten books.

Barefoot

Cherry uses the metaphor barefoot discipleship to describe a “passionate- humility, a Christlike attitude that is down-to- earth, full of live, vulnerable and transformative ” (21). His metaphor challenges us to remove the boots and shoes that protect us, inculcate us, desensitise us, from the world around us.

Take off your shoes

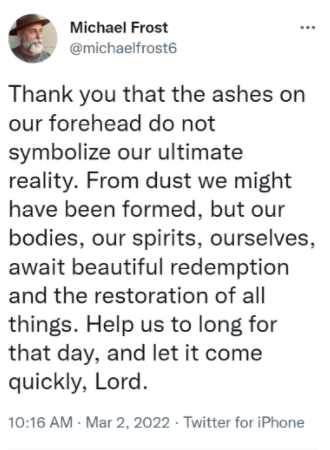

Ash Wednesday is an act of metaphorically taking off our shoes.  The ashes remind us, not just of our mortality and the fragility of life, but they point forward in hope. Australian missiologist Mike Frost summed it up neatly in a tweet when he wrote.

The ashes remind us, not just of our mortality and the fragility of life, but they point forward in hope. Australian missiologist Mike Frost summed it up neatly in a tweet when he wrote.

“Thank you that the ashes on our forehead do not symbolise our ultimate reality. From dust we might have been formed, but our bodies, our spirits, ourselves, await beautiful redemption and the restoration of all things. Help us to long for that day, and let it come quickly. Lord.”

Too many ashes

The ashes of Ash Wednesday are not the only ashes visible to us this year. Glib Mazepa, a resident in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second city spoke to reporters of life under attack from Russian missiles:

“they will just bomb the whole city to ashes”.

Ashes… too many ashes, too much war, too much death, too much destruction and loss. It can all feel too much to bear.

Ultimate Reality

Ashes …too many ashes, and yet the ashes of war mingle with the ashes of Wednesday. They remind us in these distressing and fear-inducing times that just as the ashes of Ash Wednesday do not symbolise our ultimate reality, so the ashes of war do not, and will not have the final word. Amid the ashes we remember hope, hope which has a name: Jesus.

Prayer

However, if we are not ‘barefoot’ there is a danger such hope could lead to indifference. ‘Barefoot hope’ does not shrug its shoulders and say, “it will be alright one day”, rather it rolls up its sleeves in active love and anticipation/exemplification of the beautiful redemption and the restoration of all things.

Being barefoot reminds us that the ground we stand on is holy, because God is Lord of all, and keeps us sensitive to what is going on around us.

Prayer helps keep us barefooted, it is the spiritual act of removing our shoes; of saying we come before God in his holiness not just with our own stuff, our own pain, but in solidarity with those we see who are also suffering and whose suffering is often much greater than ours.

A cry of holy discontent

In prayer we cry out to God, not just for ourselves, but for others. We cry to God that there would be peace, that rockets, and bombs would stop. That soldiers would return to their families, and weapons of war transformed into weapons of life and fruitfulness (Isaiah 2:4).

In prayer we express a holy discontent with the world as we presently encounter it as an expression of our love of God and love of our neighbour.

Breaking down barriers

Love and the breaking down of barriers of hostility is a significant theme of Paul’s letters. I detect something of this theme in Galatians 5: 1- 12 which we will look at on Sunday.

This section of Paul’s letter opens with the famous words “For freedom Christ has set us free”.

But what does freedom in Christ mean? What is it we are freed from, and for what are we freed?

I wonder what your answers are to these questions and what difference this makes in our daily interactions with people?

The only thing …

If verse 1 is the verse that makes the headlines, it is verse 6 that has stopped me in my tracks and grabbed my attention. I’ve found myself reading and re-reading the words of the second half of this verse:

“the only thing that counts is faith working itself out in love”.

What does this look like for us? What could and should this look like?

Grace and peace.

Brodie